A few weeks ago, I was toasting the last episode of the television series “Justified,” based on characters by the crime writer Elmore Leonard. The hero is a federal marshal, Raylan Givens, and in the seven year run of the show, he became my favorite TV tough guy.

Not John C. Elliott, but Timothy Olyphant, who played U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens in the recently-completed series “Justified,” based on characters created by Elmore Leonard. FX Network promotional photo.

A day or two later, I was looking something up in Stephen D. Cone’s Biographical and Historical Sketches: A Narrative of Hamilton and Its Residents (1896) , and stumbled upon a passage reminding me that Hamilton had its own tough guy marshal back in the day, a slave chaser named John C. Elliott.

His earliest claim to fame was as the man who most likely killed the founding Mormon prophet Joseph Smith while his tribe was making its way West. Having been expelled from Ohio and Missouri, the Mormons founded the city of Nauvoo in Illinois in 1839. By 1844, the city had grown to over 15,000, bigger than Chicago at the time, and Smith’s popularity was such that he decided to make a run for the Presidency of the United States.

It’s not clear from Cone and other sources how Elliott got called into service. Some Mormon lore attributes the murder of Joseph Smith to the Masons. According to Junius and Joseph by Robert S. Wicks and Fred R. Foister, a book regarding Smith’s presidential aspirations and assassination, Elliott spent the early 1840s as a woodcutter, clearing land between Hamilton and Cincinnati. He helped Jacob Burnet, a U.S. Senator and prominent Mason, in a land dispute and was thus owed a favor. In 1843, he went to Warsaw, Illinois, near Nauvoo, posing as a school teacher but working undercover for the U.S. Marshal Service.

Another Masonic connection could be that William Chittendon, who was among a group of militiamen to assail the jail that held Joseph Smith that fateful night. Chittendon was from Oxford and his father, Abraham, was the founding master of the Oxford Masonic Lodge. He and Elliott were about the same age. But true to the oath of silence sworn by the assailants, Chittendon mentioned no names.

Cone said that “a secret national call was made for men in the adjoining states to come forward and expel the Mormons,” which may support the Masonic theory, and John C. Elliott of Hamilton answered the call.

Cone described Elliott as “bold, courageous and brave, a man perfectly devoid of fear.” Before he left for Illinois, he visited Rossville’s ax-maker William C. Stephenson, who lived on Boudinot Street, now Park Avenue, to borrow a rifle made by Jacob Neinmeyer of Trenton.”

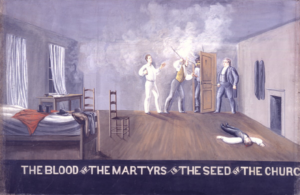

“Interior of Carthage Jail” by C.C.A. Christensen, Brigham Young University Museum of Art, public domain

The Nauvoo Neighbor, cited by Wick and Foister, said that when he arrived in Nauvoo, Elliot “looked to be a man of some twenty six or eight years; nearly five feet eight inches tall; stoutly built and athletic. He had on a jeans coat with large pearl buttons, which was untied at the upper part of his breast in a careless manner. The pants … were considerably tattered. This dress was covered by an overcoat, cut from a green Mackinaw blanket. When he doffed his white nutria hat, it disclosed a prominent forehead and a rather disordered head of black hair. His countenance was dark; his eyes were hazel and sunk to a considerable depth in his head, over which jutted out his heavy dark eyebrows, which a continual scowl knit closely together, giving him at once a savage and heartless look… he flourished a pearl-handled dirk knife, which he plied with considerable dexterity in the cavity of his ample mouth, which filled the office of a toothpick.”

Before the raid on the jail, Elliott ran into some trouble trying to serve a warrant on a man named Avery and was arrested, charged with kidnapping. He escaped custody and was apparently not pursued.

Cone wrote, “On his arrival he found that Joe and Hyrum Smith and members of the Nauvoo council had been committed to jail on the charge of treason. The jail was a large two-story stone building, a portion of which was occupied by the jailer, and the remainder of the interior, consisting of cells for the confinement of prisoners and one large room. The Smiths were confined in the cells, but were finally transferred to the large room. Governor Ford ordered a guard placed around the jail for protection of the prisoners.

Carthage Jail today, Deseret News, Creative Commons

“The Carthage Grays, a military company one hundred strong, was stationed in the court house square for the purpose of repelling an attack on the jail and the prisoners confined therein. The conspirators, who numbered two hundred brave and determined men, communicated with the Carthage Grays, and it was arranged that the jail guard should have their guns charged with blank cartridges and fire at the attacking party as it neared the jail.

“For his cool and daring bravery, John C. Elliott was selected as one of the advance assailants. The attacking party came up and scaled the picket fence around the jail; were fired upon by the guard, which was immediately overpowered, and the assailants opened the jail. The jail door was battered down, and as it burst open, Joe Smith shot three of his assailants. At this time a number of shots were fired into the room, Smith attempted to escape by jumping from the second story window and fell against the curb of an old fashioned well. The fall stunned him; he was unable to rise, and while in a sitting position, the conspirators dispatched him with four rifle balls through the body. The rifle that John C. Elliott carried ran forty-four to the pound, which was the largest bore in the attacking party. Upon examination of Smith’s body, it was found that John C. Elliot had fired the fatal shot.

“After the assassination of Joe Smith the excitement at Nauvoo was at fever heat. John C. Elliott and his confederates in the shooting were arrested. Nauvoo was not deemed a safe place for their incarceration, owing to the bitter Mormon feeling against the Gentiles. Accordingly, they were spirited to Jacksonville, where they were liberated by a mob. No effort was ever made to apprehend them, and John C. Elliott returned to Hamilton, where he played an important part in the drama of passing events. He was a terror to evil doers, and in the performance of his duties as United States Marshal and City marshal of Hamilton made enemies by the score, and enemies of a most dangerous class.”

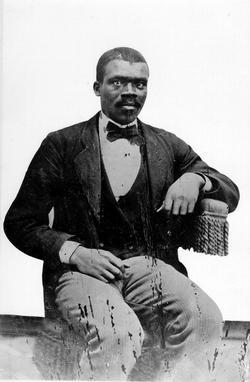

Elliott went on to be a slave chaser, and suffered many close calls and even assassination attempts. One of his more famous cases was that of the escaped salve Addison White, detailed in an article “The Rescue Case of 1857” in the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, (January 1907).

Addison White portrait wikipedia.org, Creative Commons

Elliott and his posse tracked White to a house in Mechanicsburg, Ohio. The escapee hid in the attic, accessible by one small hole in the ceiling in the room below. Since his escape, he had learned how to shoot a pistol, and sat in the attic with his gun pointed at the entrance. Undaunted, Marshall Elliott climbed the ladder and poked his head through the opening. Fortunately, he held his rifle in front of him, and White’s bullet glanced off its barrel and grazed Elliott’s cheek and took a small piece of his ear.

By that time, the people of Mechanicsburg gathered outside the house, vastly outnumbering the federal posse, and the arrest of Addison White was abandoned for a time. Before the issue was settled, Elliott faced charges of assault with intent to kill against a county sheriff, but the charges were eventually dropped.

On another occasion, he chased a runaway slave to the house of a Cincinnati newspaper editor. That man, too, barricaded himself inside. Elliott managed to gain admission through a transom, but received two good stab wounds from the slave’s Spanish dirk. They were serious wounds, but Elliott recovered.

He also served as Hamilton’s town marshal in the days before there was a proper police department, and when the Civil War broke out, Elliott enlisted in Company F, Third Ohio. It was during this service that the marshal reached a rather inauspicious end.

“While his company was encamped near Tuscumbia, Ala., in the fall of 1864,” Cone wrote, “he was engaged in a friendly wrestling match with one of his comrades. He was thrown violently to the ground, rupturing a blood vessel and dying almost instantly.”